Decision Point: Reality or Opponents

- Sep 26, 2025

- 8 min read

Article no. 1: “For 364 days out of the year most of the world lives and works in monarchies not democracies, and we don’t know the difference.”

Monarchy Thinking – Choosing one person to make the final decisions.

Democracy Thinking – A group of people collaborating to solve problems.

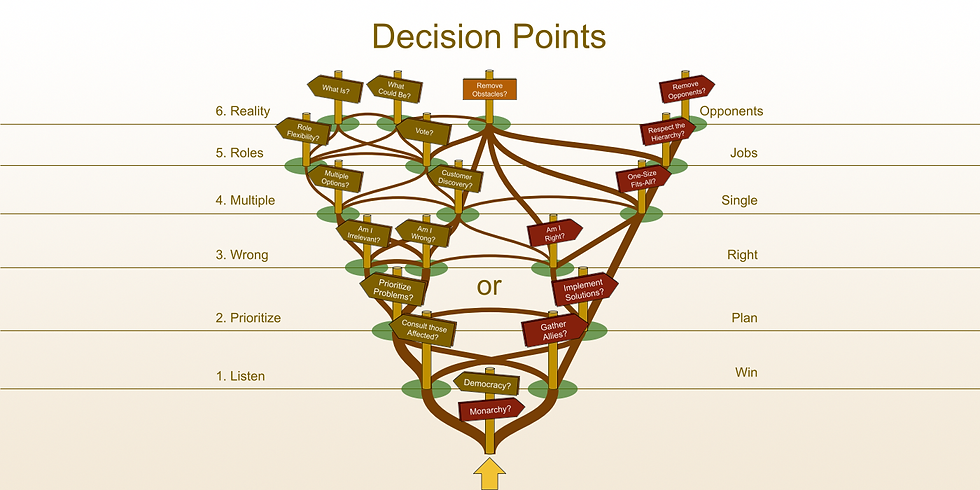

The 6 Decision Points of democracy or monarchy:

After winning allies and building plans for a single solution to be executed by the hierarchy, Monarchy Thinking is almost guaranteed to arrive at a single conclusion. If things aren’t going as planned, remove opponents who are standing in your way.

At this late stage in the decision process, the only change strategy left to us is shifting from removing opponents to removing obstacles. If we see people as standing in our way, it’s logical to want to remove them. When we redirect attention to the circumstances behind people’s choices, we unlock one final decision point.

There are multiple great techniques for shifting this perspective. One is so ubiquitous, we may forget that it’s designed for this purpose, the Kanban. The other has a few different names, but they all center around the same concept, “no blame”.

Our Last Resort Inside Monarchy Thinking

When all else has failed, or we are joining a project at the end of its lifecycle, it’s near impossible to change course in any substantial way. One way to deal with this is to wait for it to end, and then start fresh. The other strategy is to help the project reach its best possible conclusion through being the type of person who removes obstacles.

Removing obstacles works in a monarchy environment because we are helping the monarch and the hierarchy to accomplish their goals. Additionally, since monarchy thinking sees their jobs as deciders, when you bring them a decision with options it can be seen as a sign of respect.

Since monarchy thinkers see their jobs as deciders, when you bring them a decision with options it can be seen as a sign of respect.

WARNING: Do not bring an obstacle to a monarchy thinker without solution options. As the famous saying warns, “Don’t shoot the messenger,” the messenger who only brings obstacles to the monarch is most at risk of being shot. Don’t connect yourself with the obstacle. Connect yourself with solutions.

CAUTION: Also do not bring an obstacle to a monarchy thinker with a single option. As mentioned in the Decision Point “Multiple or Single”, if our solution is not what the monarch would have done, they will question our judgement and that could work against us. Bringing multiple solutions not only shows initiative and flexibility, but positions the monarchy thinker in their coveted role of Decider.

Bringing multiple solutions not only shows initiative and flexibility, but positions the monarchy thinker in their coveted role of Decider.

When done right, bringing choices to the table puts us in the category of allies and can also help us (and our colleagues) to keep our jobs. Even if we cannot execute the solutions ourselves, sharing details about multiple solutions at least moves us out of the opponents category. The Kanban community is fond of saying, “If you can’t remove the obstacle, make it visible.”

“If you cannot remove the obstacle, make it visible.”

Technique: The Kanban Board

Whenever I say Kanban these days, I can’t help but think about a friend from Japan chuckling to himself one day. When I asked, he shared his amusement that English speakers call it a Kanban Board. “‘Kanban’ means ‘board’,” he mused. “It’s like saying, ‘The board board.’” Of course, I think most of us think of Kanban as a framework, and those classic columns as the “boards from the Kanban framework.” So now it also makes me chuckle when talking about discussing the “board boards,” but I don’t plan to stop.

If you’re less familiar with Kanban boards, it’s helpful to know that they are based on the Theory of Constraints as covered in the book, “The Goal” by Eliyahu Goldratt. I like to summarize it through two principles. Principle no. 1 is that the speed of any system is exactly equal to its slowest step. Principle no. 2 is that to find the slowest step, look for the biggest bottleneck, i.e. the largest pile of work that is ready but cannot be done because the next step is too busy.

The speed of any system is exactly equal to its slowest step.

If we optimize any other portion of the system except the biggest bottleneck, we will not see any improvement in final outcomes. Any other optimization will be absorbed by the system until this biggest bottleneck is unclogged and allowed to flow faster. If we want to find the biggest bottleneck in our system, we have to make all of the wait times in the system visible. The columns of a Kanban Board are designed to visualize these bottlenecks.

I’ve heard people quote “Kanban rules” that get in the way of this principle, like “You should never have a ‘Blocked’ column.” I think static rules like these are irrelevant, and the core principles are what really matter. If a ‘Blocked’ column helps you identify the biggest impediments and remove them, use it. I have worked with teams who have made it a policy to treat Blocked items as highest priority and clear out the Blocked column as fast as possible. Used in this way it is useful, but if it causes your biggest bottlenecks to be ignored, then it should go away.

Sometimes I’ll create an entire Kanban for leadership where every card on the board is an impediment identified by a team. We call them “Escalations Boards” and they help to visualize the bottlenecks of leadership requests that go unaddressed. If leadership asks why something is taking so long, we divert attention away from blaming team members, and redirect focus to the matching card on the Escalations Board along with the age of how long that escalation has been sitting without being addressed. We make the connection that we want to go faster, but the solution is not within our area of control.

Democracy Thinking Versus Monarchy Thinking

So what about Democracy Thinking? If we have chosen the decision points for Democracy Thinking along our path, where does that lead us? First, Democracy also identifies obstacles standing in the way and addresses them, openly and honestly.

Where Democracy Thinking goes the extra mile is in separating people from the obstacles. Where Monarchy Thinking looks for people to blame for problems and obstacles, Democracy Thinking believes that it is the design of the system itself that causes people to act one way or another. If we don’t like the actions that people are taking, we have to look at how the system is structured to encourage them to take those actions. Change the system, and the same people will make different choices.

Change the system, and the same people will make different choices.

Democracy Thinking replaces blame with questions: “What is?” “What could be?” “What stands between what is and what could be?” “If we change the system, what problems will we solve? What problems will we create? Which problems are more important?” In these ways Democracy Thinking is more concerned with uncovering and understanding the complex realities of life. Through constantly learning more about reality, it is better equipped to solve more problems at the same time, with better solutions, in ways that help more people and hurt fewer.

Democracy Technique: No Blame Culture

Another great technique in this category which is used by Democracy Thinking organizations is the “No Blame Culture”. “No Blame” is often originally credited to the aviation industry in the 1980s. High profile failures exposed that people were afraid of retribution so they did not report problems until it was too late. Removing blame provided psychological safety for discussing problems, and finding better solutions faster. With the returning struggles of hidden quality problems in organizations like Boeing, it seems like the aviation industry is having to relearn those lessons again, and may not be the best source of ideas for the time being.

There are other versions of “no blame”. I first learned “no blame” through usability testing, where we were not allowed to blame the customer for anything. We had to identify what in the design was leading the customer to use it in unintended ways. Marshall Rosenberg introduced alternatives to blame in his book, “Nonviolent Communication,” released in 1999. I enjoy his techniques, but I have also seen them inspire major resistance, so I only use them selectively. James Reason used the same ideas as foundational to his concept of a “Just Culture” in his 1997 book, “Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents”. “No blame” has also become a core tenet of the DevOps movement.

Democracy Technique: No Names

The most effective introduction to “No Blame” that I have seen is the “No Names” variant. When analyzing anything, you simply are not allowed to use anyone’s name. You must find another way to describe what happened instead of, “<person> did this, and it caused <problem>.” The first few times people do it, it’s hard, but eventually it becomes easier. In very little time people get practice at identifying actions and circumstances that lead to problems and impediments, and learn how to separate those from the people who may have been involved, but who are actually independent of the process steps which are creating the biggest bottlenecks.

What’s Next

One last benefit of making a list of obstacles and options is that it forms a fantastic foundation for a list of Prioritized Problems that you can use in the next project! Spend your time listening in your current project to real people in real examples and document their experiences. They may not do you any good for the current project, but they will be great research for next time.

This wraps up the 6 Decision Points of Democracy Thinking and Monarchy Thinking. I’d be curious to hear in the comments or by direct message which Decision Points you think are going to be the easiest for you to use, and which will be the hardest? Do any of them not make sense, or seem unrealistic? Do you foresee any problems that they might cause? Are they more or less important than the problems that the decision point aims to solve?

There have been a few questions building up in response to these articles, so I may address them in more detail in the next articles. I will also share some examples of how to connect these 6 decision points together from end to end, demonstrating how to “think different” and consciously choose entirely different outcomes in the same organizations and with the same people, simply by changing the system in a way that redirects people to make different choices.

As usual, if you like where this is going or you're also fascinated with how to build a better future, subscribe, and please share this with others who you think should join the discussion.

Comments